Ethics and public health of rebuilding Gaza’s health system. Ética y salud pública en la reconstrucción del sistema sanitario en Gaza. ENG ESP

Social justice, human rights, and dignity. Justicia social, derechos humanos y dignidad

Abstract

As public health practitioners with experience of working in conflict zones, including in the Gaza Strip, we felt compelled to write this Commentary. The relative silence of the international public health community regarding the ongoing mayhem and genocide by Israel in Gaza has been deafening. In stark contrast, medics from Gaza and the region have responded massively both with pleas for an end to the genocide and also by showing us how they are coping with bare essentials in a largely destroyed health system, at the epicentre of the conflict illustrating their deep commitment to preserving life in the midst of a genocide. The voice of the medical community in the global North must rise and change so that a North-South divide on the value of human life does not evolve into a 21st century norm. This major ethical challenge is not just for Gaza but for the global public health community. We explore the ethical imperatives and immense challenges of rebuilding Gaza’s health system postconflict. Since the submission of this paper in May 2025, a ceasefire was called for in Gaza (October 10, 2025), but relentless destruction continues with impunity. Subsequently, the number of deaths, injured and displaced people have increased substantially, but this data could not be included in this commentary. However, the major challenges of rebuilding Gaza’s health system will remain at the forefront of any efforts for reconstruction.

Keywords: Gaza, health system, rebuilding, ethical challenges

Overall aim

Writing a Commentary, as Gaza lies in ruins facing a total blockade and human-made starvation for more than several months, is a major challenge. But since most Gazans have little intention of leaving their land, it is important for the public health community among others, to show solidarity and look at the future, however dire may the current situation be. We explore a future that prioritises support for the “living capacity” of Gazans through rebuilding of community networks for health and psychological well-being.

Whilst the whole of Palestine has faced the wrath of a settler–colonial state, this Commentary is focused on Gaza. The experience of Gazans, in addition to occupation, is distinguished by a suffocating siege for 17 years and now a genocide. We suggest that the devastation of Gaza, with its unique characteristics, may be addressed through the lens of social justice, human rights, and dignity, as key elements in re-building its health system.

Introduction and background

The situation in Gaza is rapidly evolving into the worst humanitarian crisis in modern memory, and international health organisations have no long-term plans for addressing the territory’s post-war needs [1].

The Gaza Strip has been the epicentre of profound humanitarian and health crises for nearly two decades. Since the election of Hamas in 2007, the region has faced a suffocating siege by the occupying power, Israel, leaving the population isolated from essential resources like clean water, food, and healthcare [2, 3]. The situation has been compounded by successive conflicts, each leaving behind a trail of devastation [2, 4]. Over the past 20 months, the intensity of the violence has escalated to unprecedented levels, leading to the systematic destruction of Gaza’s infrastructure, particularly its healthcare system, on a staggering scale, with reports indicating the loss of more than 55,000 lives, rising daily, and more than 124,000 injuries. There are up to 30,000 people still unaccounted for, buried under the rubble of bombed buildings. These numbers are rising daily [4, 5, 6, 7] .

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 94% of hospitals in Gaza are damaged or destroyed [8]. Those providing basic functions are overwhelmed. From hospitals to food, water, and sanitation all remain largely inaccessible to the majority [9]. A major challenge has been the repeat displacement of 90% of the population that makes access to any kind of care impossible. The destruction of lives and of the health system is not just an ethical issue, but a political one as described by Shahvisi [10], among others [11]. Compounding the complicity of several states, particularly in the West, is the silencing of public anger calling for a ceasefire and an immediate end to genocide, worldwide. The laws of war, under the Geneva Convention [12], do not allow attacks on health centres and health workers, and do not permit blocking the supply of medicines and equipment. Yet the western powers have been complicit in Israel’s decimation of health infrastructure and emergency care, killing of more than 1000 health workers injuring many others to date, and blocking of quality healthcare for pregnant women and children. The only rationale offered for Israel’s genocide of civilians in Gaza is that of a reaction to the bold kidnapping and killing of soldiers and civilians by Hamas and other resistance groups in Gaza, on October 7, 2023, in an unprecedented strike into Israeli-occupied territory.

Health crises in Gaza: A long-standing issue rooted in occupation

The public health context in Gaza cannot be gauged without understanding the brutal occupation of the Palestinian Territories by Israel, for more than 75 years. Since Hamas was elected to power in 2007, Gaza has experienced a sharpened assault, including a total blockade, from land, sea and air, which has meant people were unable to work, trade, farm, make goods or import and export them [2, 3, 4]. Enforced destitution has been its outcome.

Gazans have been forced into total dependence on aid with a damaging effect on both physical and mental health, after eight wars on the Gaza strip since 2008. The war of 2008, continued until January 2009, then recurring attacks in 2012, 2014, 2019, 2021, 2022, and finally the current war in 2023-2024 [2]. Each one of these wars inflicted deaths, injuries and damage to infrastructure, in particular to the health system, the focus of this Commentary.

Before delving into the reconstruction of Gaza’s healthcare system, it is important to acknowledge the long-standing health challenges faced by the population as a result of the repeated violence and blockade by Israel. For years, the indicators have been poor, with hospitals operating with outdated and under-equipped facilities. The health system has been under constant strain with over-burdened health professionals, many leaving, and the local population having limited access to life-saving treatment and medications. Even prior to the current conflict, as a result of total isolation, more than 80% of Gaza’s population was living in poverty, and over two-thirds were food insecure and dependent on international assistance. Water and sanitation conditions were already dire, with frequent shortages and pollution, exacerbated by repeated bombing, including of water treatment and desalination plants. As a result, the population has been exposed to infectious diseases, malnutrition, and other preventable health issues worsened by extremities of temperatures, especially during the summer [2, 13].

The impact of the current conflict on Gaza’s health system has been a catastrophic one. Less than half of Gaza’s hospitals are even partially operational, and less than 40% of primary healthcare centres are operational. The information from WHO on May 22, suggests that more than 94% of Gaza’s hospitals are either damaged or destroyed [8]. Clearly, data on deaths, injuries and destruction, which are ongoing, shifts on a daily basis.

Medical evacuations abroad are slow, and specialised healthcare is unavailable. The destruction of health infrastructure, alongside the rise in infectious disease, malnutrition, and food insecurity, has compounded the suffering of an already vulnerable population [7, 14, 15]. In May alone, killings, attacks and displacement by Israel have shocked humanitarian institutions and the public at large. More than 600,000 displaced, 28 aid workers killed, more hospitals rendered dysfunctional in the face of overwhelming need. All of this has taken an unimaginable toll on the physical and mental health of the population [14, 16]. In one week alone, from May 22-28, 456 Palestinians were killed and more than one thousand injured including 28 aid workers.

Calls by the WHO for the protection of civilians, of hospitals and health workers under international law have been repeatedly ignored by Israel [17], whilst the growing numbers of injured without treatment and who will end up with life-long disabilities is nothing short of a stain on humanity.

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) estimated that 58,000 people (2.6% of the population) were suffering disability prior to the current conflict [18]. A majority of these were injured from previous conflicts. If one adds the numbers of those injured from the current war, estimated in May 2025 at 124,000 plus [9], it amounts to almost 9% of the population of 2.2 million. Often in conflict zones, data is underestimated and most of those injured will remain without treatment. This highlights not just a genocide but a moral failure of the international community1 to prevent relentless destruction en masse and the life-long suffering of the civilians of Gaza.

The strain of displacement and the need for shelter

One of the immediate challenges Gaza faces is the displacement of nearly two million people, which constitutes 90% of the population. The destruction of over 80% of residential accommodation has forced families to seek shelter in temporary tents or in the rubble of their homes. With winter temperatures often dropping below freezing, the living conditions are dire. Basic services, including access to water and sanitation, are virtually non-existent, exacerbating health risks particularly of infectious diseases that have become widespread [7, 19, 20].

The urgent need for adequate shelter and access to clean water, food, and sanitation cannot be overstated. These basic needs are fundamental for survival and form the foundation for any efforts to rebuild the health system in Gaza. However, given the extensive destruction of Gaza’s agricultural land, which was a primary source of local food production, food insecurity remains a critical issue. The deliberate withholding of humanitarian aid has caused widespread hunger and a growing number of famine-related deaths, with several hundred mostly children. Rebuilding the agricultural infrastructure will be essential to addressing food shortages and ensuring long-term restoration of food security and population health in the region [9]. The relentless destruction and ongoing blockade of Gaza has made a mockery of articles protecting human life and dignity under the Geneva Convention [4] and of International Humanitarian Law (IHL)2 in general. There is a growing consensus that the laws meant to protect civilians under the Geneva convention, in particular IHL, are at risk of collapse. Whilst several previous conflicts have shown a blatant disregard for the protection of non-combatants — women, children, and also of civilian infrastructure — nowhere has this been more acutely evident than in the current conflict in Gaza [12].

Rebuilding Gaza’s health system and planning for a future

The scale of the healthcare system’s devastation up to May 2025 is detailed in the most recent update from United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) [9]. The inevitably slow rebuilding of the healthcare system will necessarily have to address all the components of the health system [21]. A huge demand for services will need to be addressed through a coordinated intersectoral action with health of the people as a fundamental priority in all policies in order to face multiple and diverse determinants of health (economic, social, environmental, cultural, etc) that the conflict has exacerbated; the first determinant being Israeli occupation [2]. Services will have to be adapted on the one side to the immediate needs of the population, while on the other developing appropriate approaches for the future sustainability of the system (for example, focus on integrated Primary Health Care and community-based essential services, universal access and equitable financing, sector wide approach) [22].

Case studies examining rebuilding health systems in different post-conflict situations emphasise that each post-conflict period is a unique one, exposing specific geographic, demographic and political challenges [21]. In terms of governance, experience shows that the initial reconstruction process is often largely driven by the agenda of uncoordinated donors and implementing agencies, posing important issues regarding lack of local ownership and long-term sustainability [21], that should be avoided from the beginning.

The reconstruction of Gaza’s health infrastructure is paramount to addressing the immediate and long-term health needs of the population. However, this will be an incredibly complex and costly endeavour, given the scale of destruction and the geographical limitations of the enclave. The challenge of the reconstruction of the physical infrastructure is possibly only comparable with the reconstruction of German cities after World War II [23], even though Gaza’s geographical, socio-economic and political conditions are unique. The rebuilding process needs to focus not only on physical infrastructure but also on the restoration of health service delivery, personnel, and essential supplies [6].

Reconstitution of the health workforce will represent a major challenge. Many healthcare professionals who once worked in Gaza have either been killed, injured or displaced, besides their distress and mental suffering preventing the proper provision of “service delivery” following the end of the conflict [21]. Thus, support to and training of local health workers in dealing with the most pressing needs of the population will be essential. Avoiding situations where unregulated, private and NGO-provided services, eventually combined with insufficient salary of public service health workers could otherwise induce the emergence of a two-tiered health system. This would hamper the establishment and development of any sustainable national health service [21] essential for Gaza, with an impoverished population.

A critical challenge lies in the treatment of the thousands of individuals who have sustained life-altering injuries, particularly children who have been subjected to ad-hoc amputations on a daily basis. Many of these individuals and, in particular children, will require long-term rehabilitation and specialised care. A coordinated international response is necessary to ensure that specialised healthcare, such as prosthetics, rehabilitation, and mental health services, is provided to those in need [24].

Once again it is a moral and ethical duty of the international community notably the medical and public health one to press for an immediate ceasefire and treatment for those injured.

The mental health crisis

Rebuilding community and relational dimensions of living was key to Gaza’s survival under 17 years of blockade. This has, been seriously undermined through systematic killing of whole families and the destruction of entire neighbourhoods. This will be among the most urgent ethical and social challenges, preceding the physical and functional rebuilding of the health system.

In this context, one of the most pressing, yet often overlooked, challenges for post-conflict Gaza are the mental health crisis. According to WHO, this is the biggest challenge facing Gaza’s population [1]. The daily bombardment, loss of family members, and destruction of communities will have left deep emotional scars on the population. Psychological trauma is pervasive, particularly among children and adolescents, who are witnessing the destruction of their homes, schools, and social networks. The long-term impact of this trauma will shape the future of Gaza for generations to come [25, 26].

While it is widely acknowledged that the most urgent need is for a ceasefire, the level of trauma in Gaza will remain for many years to come. There is anecdotal evidence that despite relentless bombing and drone attacks, community-level initiatives are attempting to address children’s trauma through play, circus-acts and street theatre [27]. However, it is unclear if any groups or institutions are able to substantially address this, besides the scale of adult trauma, particularly of women or the elderly who, other than children, are among the most vulnerable.

What was once a meagre but functioning mental health service in Gaza has shrunk to a bare minimum, due to daily bombardment, the lack of safety or security and the loss of supplies.

Jabr and Berger suggest that the massive loss of the health workforce including those working as psychologists, is a core to the prevalent trauma and best addressed through community-based initiatives. Under the current circumstances, individual treatments they argue, are not feasible. They recommend the Mental Health Gap programme of the WHO focused on community-based support and training of non-specialised workers [25, 28]. The importance of strengthening community networks for social support as a key method of addressing the range of trauma in the Gaza strip, is reiterated by Diab et al [29].

In addition, rarely mentioned is the trauma of health professionals. From doctors and surgeons to nurses and paramedics, not only have many been targeted, but a large number have been abducted, tortured and forcibly disappeared. Medics have had to witness countless deaths that were avoidable and which they could not treat.

Paramedics have had to rescue children without limbs including those with multiple injuries, with little chance of treatment or survival. In this context of utter devastation, we question the norm often adopted by outsiders that Palestinian “resilience” is an eternal attribute of those living under occupation and now genocide. Most do not want war and would like to live in peace.3

Mental health and psychosocial support (MHPSS) services provided by international agencies such as United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), are also stretched to their limits. The intensification of conflict with a total blockade by Israel since early March 2025, has worsened the situation manyfold. According to UNRWA, the mental health crisis in Gaza has intensified, with urgent need for comprehensive and long-term MHPSS programmes. The lack of access to critical mental health services, including urgent medication, due to severe restrictions on humanitarian aid and the collapse of the healthcare system, has left many individuals without support. The situation is compounded by the loss of community structures and the interruption of educational services, vital for rebuilding social cohesion [6, 16, 25].

Articles in Lancet Psychiatry highlight the acute challenges of providing mental health interventions in Gaza, especially in light of the inevitable prioritisation of immediate survival needs such as food, water, and shelter. Access to telemedicine is limited due to internet disruptions, and psychiatric facilities have been damaged or are lacking in essential medications. The international community must recognise the importance of mental health in the recovery process and prioritise the rebuilding of mental health services as part of the broader health infrastructure [16, 26].

Raising resources: a legal and ethical challenge

The WHO estimated the need for emergency funding in Gaza of $204.2 million for 2024 alone. Their calculations for the long term extended to several billion USD [1].

This is where we have a major challenge in terms of how best to raise funding. Whilst addressing mental health and community support will require innovative solutions and may not immediately need a major injection of funds, the rebuilding of infrastructure will do so. The loss of thousands upon thousands of lives in death and injury is incalculable. For social and physical infrastructure however, an ethical and just approach in our view is essential. It would be for the international community to strive for effective compliance, apply fairly tenets of IHL and implement the recommendations of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) as well as resolutions adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) [30], as per the laws of conflict. Given the systematic and deliberate destruction of civic infrastructure, from residences to schools, hospitals, universities, water treatment and electricity plants, then only Israel is liable. Despite the different context, we use as analogy the proposal by the West that the rebuilding of Ukraine in the future can be undertaken through use of frozen Russian assets [31]. We believe that to be ethically appropriate and coherent, the same rule should apply to Israel, ie, freezing its assets and using them for the reconstruction of Gaza, in a conflict that has disproportionately (and historically) targeted civilians [17]. Israel’s settlement policies, property expropriation, and other occupation-related practices constitute wrongful acts under IHL. Notably, through its 2024 advisory opinion, the ICJ affirms Israel’s obligation to end the occupation, evacuate settlements, and restore confiscated land and property [32].

Tentative solutions and the path to sustainable health in Gaza

The road to rebuilding Gaza’s health system will be a long and difficult one, but several key actions can help pave the way for a sustainable recovery. In post-conflict situations, the reconstruction of the pre-existing health system is reportedly considered to be the more viable option, rather than protracted emergency relief programmes, and the post-conflict environment may also be seen as a “window of opportunity” for reform [21]. Indeed, we agree with Alkhaldi and Alrubaie [5] on the imperative of rethinking the health system and adopting a new and strategic national, inclusive integrated approach, to meet the immediate and long-term needs of the population.

Health interventions cannot focus on physical health alone, but must include mental health, quality of life, suffering, and well-being, within the general context of life in the Gaza Strip in all its aspects. In the immediate aftermath of a ceasefire, basic needs and freedoms needs to be addressed, among others: access to clean water suitable for drinking and human use; unrestricted entry of food; return of farmers to their lands, and immediate technical assistance (including seeds and irrigation water); freedom of movement for Gaza residents, including allowing them to seek treatment outside the Strip and abroad; unrestricted entry of medicines and medical equipment, and in-kind assistance, especially to provide adequate shelter and related services, rapid restoration of schools and the resumption of studies as soon as possible, and the return of children to their daily lives without the constant threat of death [2].

In the reconstruction of the unique condition of devastation of Gaza, we believe that from a public health perspective, some aspects may be prioritised:

1. Ensuring the revival of primary healthcare: Rebuilding Gaza’s health system must start with a focus on primary healthcare (PHC). This means not only restoring damaged facilities but also ensuring that they are adequately equipped and staffed to provide basic health services, including maternal and child health and chronic disease management and most important, support for rehabilitation of those at all ages injured from conflict. Mobile health units need to be widely deployed to address immediate healthcare and health promotion needs in areas where access to clinics is unavailable.

2. Rebuilding mental health services: Mental health needs to be treated as a priority in the rebuilding process. This involves rebuilding mental health services, ensuring the availability of medications, and providing community-based mental health support. Special attention must be given to vulnerable groups, including children, the elderly, and individuals with pre-existing psychiatric disorders.

3. Community involvement: Any efforts to rebuild Gaza’s health system must involve the local population. Community consultation is vital to understand the specific needs of different regions within Gaza and ensure that reconstruction efforts are aligned with local priorities. Empowering local communities to take an active role in the rebuilding process will help create a more resilient and sustainable health system in the long term.

4. Coordinated international response: WHO and other UN agencies should play a leading role in coordinating international reconstruction efforts in the health sector, ensuring Palestinians authorities, including the Ministry of Health of Gaza have full ownership of the process. This includes assessing the specific needs, prioritising interventions, and ensuring that medical supplies and personnel are brought in without delay. Clear roles should be established at both the local and international levels to ensure alignment and harmonisation of aid, avoid duplication and maximise efficiency.

5. Sustainable financing: The cost of rebuilding Gaza’s health system will be an enormous one. Estimates from WHO for immediate emergency support for healthcare run into the millions; whilst for the longer term, into billions [1]. Innovative financing mechanisms, such as the use of frozen assets or international reparations for damages caused by the conflict, should be explored. At the same time, the international community must commit to long-term unconditional financial support to ensure the sustainability of health services in Gaza and its protection under international law, needs to be enforced.

Conclusion

To stop the war on the people of Gaza is the first and most urgent moral and political obligation for the international community. Restoring human rights and valuing the life of Palestinians as equal to all others cannot be stressed enough. The destruction of the health system has been a primary tool to perpetuate genocide by Israel in Gaza. Rebuilding Gaza’s health system is therefore essential, albeit a complex task that will require community engagement together with international cooperation, strategic thinking, planning, and long-term investment. Most of all, collective action is needed to enforce international laws for the protection of health workers, of civilians, and of the health infrastructure that has to date been blatantly ignored.

It will take political will, a commitment to medical ethics, human rights and an acknowledgment that everyone has a right to life with dignity, as an impetus for the international community to demand this urgently for Gaza. The devastation caused by the ongoing conflict has left the population vulnerable to major health challenges. However, with a coordinated response, wide participation of the people of Gaza, a focus on sustainable health solutions, and international ethical and financial commitment, it will be possible to rebuild a health system that will work for Gazans immediately and in the long term.

Notes:

1 The term “international community” is commonly used as a generic reference to the collective efforts of the world in facing global issues. Obviously a formal “international community” does not exist as such, but the term is generally accepted in the political and social sciences. However, we may precisely refer to “the laws of conflict” using instead: International Humanitarian Law (IHL) or the Law of Armed Conflict (reference to Geneva Conventions and The Hague convention, in application to this context for the reconstruction of Gaza.

2 International Humanitarian Law (IHL) or the Law of Armed Conflict, with reference to Geneva Conventions and The Hague convention. See: https://www.icrc.org/sites/default/files/external/doc/en/assets/files/other/what_is_ihl.pdf

3 It is clear that whilst ‘Sumud’ is part of a collective Palestinian consciousness for survival and resistance against occupation, in this view it does not justify a normative adopted by outsiders or observers of the Palestinian struggle, that ‘resilience’ is the key to their survival. Global recognition that the occupation must end to enable Palestinians to live in peace without ongoing death and destruction, can be the only acceptable norm.

Authors: Kasturi Sen (corresponding author — senk83434@gmail.com, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4257-5211), Wolfson College (CR) Oxford, North Oxford, ENGLAND; Eduardo Missoni (eduardo.missoni@unibocconi.it, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2296-4145), Academic Fellow, SDA Bocconi School of Management, Milano, ITALY.

Conflict of Interest: None declared Funding: None

To cite: Sen K, Missoni E. The ethical and practical challenges of rebuilding Gaza’s health system. Indian J Med Ethics. Published online first on October 30, 2025. DOI: 10.20529/IJME.2025.081

Submission received: May 6, 2025

Submission accepted: September 17, 2025

Manuscript Editor: Sayantan Datta

Peer Reviewers: Parth Sharma and an anonymous reviewer

Copyright and license

©Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 2025: Open Access and Distributed under the Creative Commons license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits only noncommercial and non-modified sharing in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- Wade G. The war in Gaza is creating a health crisis that will span decades. New Scientist. 2024 Mar 11[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2421388-the-war-in-gaza-is-creating-a-health-crisis-that-will-span-decades/

- Husseini A. On the Edge of the Abyss: War and Public Health in Gaza. Policy Paper, Institute for Palestine Studies. 2024 Jan 30[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/1655128

- Musa A, Crawley J, Haj H, Ingish T, Maynard N. Gaza, 9 years on: a humanitarian catastrophe. Lancet. 2023 Dec; 402(10419): 2292-2293. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(23)02639-9

- Arawi T. War on Health Care Services in Gaza. Indian J Med Ethics. 2024 Apr;9(2) NS: 130-135. https://doi.org/10.20529/IJME.2024.004

- Alkhaldi M, Alrubaie M. Road map for rebuilding the health system and scenarios of crisis path in Gaza. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2025 Jan;40(12): 241-253. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3861

- Balkhy H, Ghebreyesus TA. A roadmap for healing Gaza’s battered health system. East Mediterr Health J. 2025;31(2):54–55. https://doi.org/10.26719/2025.31.2.54

- Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Humanitarian Situation Update #284 Gaza Strip (EN/AR). OCHA; 2025 Apr 30[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/humanitarian-situation-update-284-gaza-strip

- World Health Organization. Health System at breaking point as hostilities intensify in Gaza. Inhouse News Release. 2025 May 22[cited 2025 May 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/22-05-2025-health-system-at-breaking-point-as-hostilities-further-intensify–who-warns

- Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Humanitarian Situation Update-Gaza strip # 292. 2025 May 28[cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/occupied-palestinian-territory/humanitarian-situation-update-292-gaza-strip

- Shahvisi A. Editorial The ethical is political: Israel’s production of health scarcity in Gaza. J Med Ethics. 2024 May 9;50(5):289-291. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme-2024-110064

- Razai MS, Barıs M, Özekmekçi Mİ, Dabbagh H, Lederman Z. The health care community has a responsibility to highlight the ongoing destruction in Gaza. BMJ. 2025 Apr 11; 389: r741. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.r741

- Poole D. The rules of war alone are not protecting health care. Health Affairs Forefront. 2025 June 18[cited 2025 May 30]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20250616.953554/full/

- Mahmoud H., Abuzerr S. State of the health-care system in Gaza during the Israel–Hamas war. Correspondence. Lancet, 2023[cited 2025 May 30]; 402(10419): 2294. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(23)02634-X/fulltext

- Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. Humanitarian Access Snapshot-Gaza Strip. 2024 October 29[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.ochaopt.org/content/humanitarian-access-snapshot-gaza-strip-september-2024

- Abuelaish I., Musani A. Reviving and rebuilding the health system in Gaza. East Mediterr Health J., 2025, 31(2):56–58. https://doi.org/10.26719/2025.31.2.56.

- United Nations Relief Works Agency, UNRWA, Mental Health and Psychosocial support (MHPSS) in Gaza after 300 days of war. Analysis. Report. URNWA: Amman Jordan, 2024[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.unrwa.org/sites/default/files/content/resources/22.8.24_-_mhpss_300_day_report_final.pdf

- UN, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel (A/HRC/59/26), 2025 May 6 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/report-of-the-independent-international-commission-of-inquiry-on-the-occupied-palestinian-territory-including-east-jerusalem-and-israel-a-hrc-59-26/

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics PCBS. Press release on the occasion of the International Day of Persons with Disabilities, 2023 Dec 3[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.pcbs.gov.ps/portals/_pcbs/PressRelease/Press_En_DisabledDay2023E.pdf

- Zayed D, Banat M, Al-Tammemi AB. Infectious diseases within a war-torn health system: The re-emergence of polio in Gaza. Letter. New Microbes, New Infect. 2024 Sep 5; 62 (101483): 1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nmni.2024.101483

- Hamdollahzadeh S., Karami C. Polio, conflict and health implications in Gaza. East Mediterr Health J. 2025 Mar 3; 31(2):138–140. https://doi.org/10.26719/2025.31.2.138

- Rutherford S, Saleh S. Rebuilding health post-conflict: case studies, reflections and a revised framework. Health Policy Plan. 2019 Apr 1; 34(3): 230–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz018

- Missoni E. Global Health Determinants and Limits to the Sustainability of Sustainable Development Goal 3. In: Flahaut, A. (ed.) Transitioning to Good Health and Well-Being, Basel, MDPI, 2022; 1-29. https://doi.org/10.3390/books978-3-03897-865-7-1

- Diefendorf JM. In the Wake of War: The Reconstruction of German Cities after World War II. Oxford University Press; 1993. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195072198.003.0001

- The New Arab. How Israel’s war has devasted the disabled community of Gaza. 2024 Oct 1[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.newarab.com/features/how-israels-war-gaza-has-devastated-disabled-community

- Jabr S, Berger E. Palestine- Meeting Gaza’s mental health crisis. Correspondence, Lancet Psychiatry, 2023, 11(1): 12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(23)00398-X

- Taha AM, Sabet C, Nada SA, Abuzerr S, Nguyen D. Addressing the mental health crisis among children in Gaza. Lancet Psychiatry. 2024 Apr; 11(4): 249-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(24)00036-1

- United Nations Economic, Social and Cultural Organisation, UNESCO, Addressing children and adolescents’ mental health through theatre in Gaza. 2024 Oct 11 [cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/addressing-children-and-adolescents-mental-health-theater-gaza

- World Health Organization. WHO mental health gap action programme (mhGAP), WHO/MSD/MER/17.6, Geneva: WHO; 2017[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/259161/WHO-MSD-MER-17.6-eng.pdf

- Diab M. Veronese G, Jamei YA, Hamam R, Saleh S, Zeyada H. Psychosocial concerns in a context of prolonged political oppression. Gaza mental health providers’ perspectives. Transcult Psychiatry. 2023 Jun; 60(3):577-590. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615211062968

- United Nations General Assembly. Adopted Resolution: Protection of civilians and upholding legal and humanitarian obligations – United Nations General Assembly 10th Emergency Special Session (A/RES/ES-10/27) 2025 June 12[cited 2025 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/resolution-protection-of-civilians-ga-es10-12jun25/

- Jones M. Explainer: How the West uses Russia’s frozen reserves to help Ukraine. Reuters. 2025 Mar 5[cited 2025 May 20]. Available from: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/how-west-uses-russias-frozen-reserves-help-ukraine-2025-03-05/

- International Court of Justice. Legal Consequences arising from the Policies and Practices of Israel in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem. Advisory Opinion of 19 July 2024[cited 2025 May 20]. Document Number 186-20240719-ADV-01-00-EN. Available from: https://www.icj-cij.org/index.php/node/204160

Israeli rape culture. Cultura israelí de la violación sexual. ENG ESP

Zionism is inherently imbued with rape culture. El sionismo como cultura de la violación

Publicado hoy.

Vídeo. "Genocidio en Palestina. Un espejo dramático que impacta en la sanidad española" Vídeo 90 min

Encuentro en Zaragoza, preparación para el Tribunal de los Pueblos sobre la Complicidad con el Genocidio palestino en el Estado español TPCGP-25.

Publicado hace 2 días.

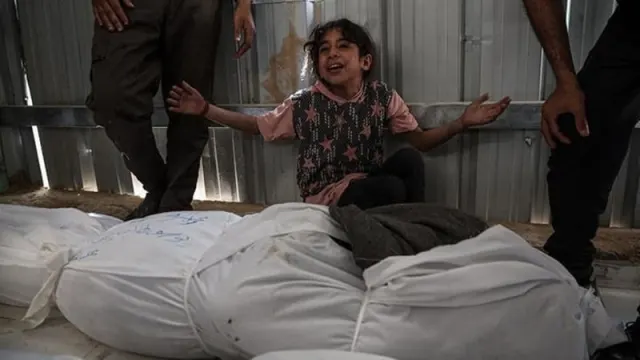

Gaza’s Orphan Crisis: 40,000. En Gaza, 40.000 huérfanos ENG ESP

40,000 children after losing one or both parents. 40.000 niños en Gaza sin uno o dos padres

Publicado hace 7 días.

Teva y el ejército de Israel (IDF). Teva and the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). ESP ENG

Teva apoya directamente el genocidio palestino. Teva directly supports the genocide against Palestinians.

Publicado hace 14 días.

ICE operations (USA) versus Israel occupation of Gaza. EEUU, policía de inmigración versus Israel ocupación de Gaza. ENG ESP

“Imperial-colonial boomerang” in action. El «bumerán imperial-colonial» en acción

Publicado el 13 de febrero.

Teva, growing global backlash. Teva, boicot creciente ENG ESP

Teva: politics and business over compassion and ethics. Teva: política y negocio sobre compasión y ética

Publicado el 10 de febrero.

"Si Francesca Albanese es terrorista, yo también". "If Francesca Albanese is a terrorist, then so am I" ESP ENG

"Una relatora de derechos humanos de la ONU, tratadа como terrorista por documentar el genocidio en Gaza". "A UN human rights rapporteur, treated as a terrorist for documenting the genocide in Gaza"

Publicado el 9 de febrero.

Vídeo, 60 sg. Dr. Hussam Abu Safiya. Lazos Rojos por la liberación de rehenes palestinos.

Campaña por la liberación de rehenes palestinos

Publicado el 7 de febrero.Ver más / See more