Paz. Israel nunca pierde la oportunidad de perder una oportunidad. Peace. Israel never misses an opportunity to miss an opportunity. ESP ENG

El temor de los líderes israelíes a la paz. Israel’s leaders fear peace.

ESPAÑOL

Los líderes israelíes temen más a la paz que a la guerra, porque la paz exigiría igualdad, responsabilidad y el fin del apartheid.

Cuando se trata de la paz, Israel nunca pierde la oportunidad de perder una oportunidad.

Durante más de medio siglo el mayor obstáculo para la paz en Oriente Medio no ha sido la ausencia de iniciativas palestinas audaces, sino la implacable determinación israelí de enterrarlas antes de que puedan echar raíces.

Una y otra vez, desde el reconocimiento sin precedentes de Israel por parte de la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina (OLP) en 1988 y su renuncia a la lucha armada, hasta las ofertas de alto el fuego de una década por parte de los líderes de Hamás, los líderes palestinos han puesto sobre la mesa compromisos históricos.

Y una y otra vez, Israel ha respondido a estos momentos no con las manos abiertas, sino con los puños cerrados, el sabotaje político y los asesinatos. El patrón es tan constante, tan deliberado, que «perder una oportunidad para la paz» ha dejado de ser un trágico accidente y se ha convertido en una doctrina calculada.

En 1988 la Organización para la Liberación de Palestina le hizo a Israel la oferta más generosa de la historia palestina. La OLP aceptó el Estado de Israel, cedió el 78% de la Palestina histórica a «un Estado judío», condenó «el terrorismo en todas sus formas» y pidió a cambio un Estado en Cisjordania, Gaza y Jerusalén Este.

Este debería haber sido el escenario soñado por Israel: poner fin al conflicto, a la Primera Intifada y a su aislamiento internacional, y asegurar su futuro en la región. Sin embargo, Tel Aviv entró en pánico.

El primer ministro Yitzhak Shamir rechazó inmediatamente el gesto de la OLP calificándolo de «loco y peligroso» y prometiendo que Israel «nunca permitirá la creación de un Estado palestino independiente en los territorios ocupados».

Su ministro de Defensa, Yitzhak Rabin, prometió utilizar «mano dura» para aplastar esta oferta de paz. El Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores de Israel activó un equipo de control de daños para desacreditar la propuesta de la OLP. El único periodista israelí, David Grossman, que se atrevió a informar sobre la decisión de la OLP fue despedido de su trabajo en la radio y atacado en la Knesset y en todos los medios de comunicación israelíes.

El Gobierno israelí y las organizaciones proisraelíes estadounidenses también criticaron a los judíos estadounidenses que se reunieron con Yasser Arafat para aprovechar su gesto de paz. Estados Unidos denegó a Arafat el visado para presentar su oferta en la Asamblea General de la ONU.

Hoy la historia se repite, ya que los países europeos intentan ofrecer a Israel una salida a su imagen gravemente dañada por el genocidio de Gaza.

El pasado mes de mayo, en Singapur, el presidente francés Emmanuel Macron describió el reconocimiento de Palestina como «un deber moral y una necesidad política», pero luego vació de contenido esa declaración al condicionar ese gesto simbólico al desarme de Hamás, su salida de Gaza y su exclusión de cualquier papel en el gobierno palestino.

El Gobierno israelí volvió a entrar en pánico y acusó de inmediato a Macron de «liderar una cruzada contra el Estado judío».

Desde entonces, Tel Aviv ha estado atacando de manera similar a todos los países que han expresado su intención de reconocer a Palestina y lo ha acusado de «recompensar» a Hamás, sabotear las negociaciones de alto el fuego y empujar a Israel hacia el «suicidio nacional».

La frenética reacción de Israel es reveladora. Los israelíes entienden que el reconocimiento es una maniobra europea para revivir la fachada de un proceso de paz, muerto hace mucho tiempo, y evitar confrontar o responsabilizar a Israel por su genocidio.

El reconocimiento no tendría ningún impacto en el avance de la creación de un Estado palestino, ni frenaría la acelerada anexión de Cisjordania por parte de Israel.

Sin embargo, incluso un simple gesto como este provoca pánico en Israel porque Netanyahu está tratando de persuadir a sus aliados occidentales de que la única solución a la cuestión palestina es la despoblación de Gaza.

Los líderes occidentales intentan culpar del rechazo de Israel al gobierno de extrema derecha de Netanyahu. Sin embargo, todos los partidos políticos sionistas israelíes, incluido el izquierdista Meretz-Laborista, han dejado clara su oposición a la solución de dos Estados.

Este rechazo no es nuevo ni es consecuencia del 7 de octubre, sino que ha sido una característica constante de los sucesivos gobiernos israelíes desde que comenzó la ocupación en 1967.

Frustrar las «ofensivas de paz» palestinas

En 1976 la OLP y los países árabes impulsaron una resolución en el Consejo de Seguridad de la ONU que pedía la solución de dos Estados. La resolución recibió el apoyo de todos los miembros del Consejo de Seguridad, pero Israel la rechazó, por lo que Estados Unidos la vetó.

En 1981 la OLP respaldó oficialmente una propuesta de la Unión Soviética para la creación de un Estado palestino en los territorios de 1967 y la «seguridad y soberanía» de Israel. Meses más tarde, el rey Fahd de Arabia Saudí ofreció a Israel la propuesta más generosa posible: Israel se integraría en la región y se le garantizaría la paz de todos los países árabes si aceptaba la solución de dos Estados.

Esta oferta se reiteró en 2002 como la «Iniciativa de Paz Árabe» y fue respaldada por 57 países musulmanes, pero Israel la ignoró.

Israel vio una amenaza en este impulso y lo consideró una «ofensiva de paz»: los palestinos se estaban volviendo demasiado moderados e Israel se estaba quedando sin excusas para mantener la ocupación.

Tel Aviv respondió con una guerra contra la OLP en el Líbano con el fin de aplicar las «presiones militares más feroces» para socavar a los moderados palestinos y hacer que la OLP adoptara una línea más dura «para detener su ascenso a la respetabilidad política».

Oslo y la farsa del proceso de paz

En 1993 Israel se vio obligado a aceptar los Acuerdos de Oslo por su fracaso en aplastar violentamente la Primera Intifada y su incapacidad para hacer frente al aislamiento internacional, la presión y el daño económico, diplomático y político resultante de su estrategia de «romper los huesos» contra manifestantes civiles desarmados y niños.

El mundo aclamó Oslo como una nueva era de paz, pero Israel introdujo suficientes lagunas en el acuerdo para evitar el fin de la ocupación. El primer ministro Rabin, que ganó el Premio Nobel de la Paz por Oslo, dejó muy claro que se trataba únicamente de una separación, no de la creación de un Estado palestino.

«No aceptamos el objetivo palestino de un Estado palestino independiente entre Israel y Jordania. Creemos que existe una entidad palestina separada que no es un Estado», afirmó.

Apartheid significa «separación», y eso es lo que ocurrió sobre el terreno. Los asentamientos israelíes crecieron exponencialmente y, durante el «proceso de paz», se trasladaron más colonos al territorio ocupado que antes de Oslo. Mientras tanto, los palestinos se vieron obligados a vigilar la ocupación israelí y a frustrar la resistencia armada, lo que hizo que el apartheid no tuviera ningún coste para Tel Aviv.

En 2000 Israel dejó claro en Camp David que lo máximo que ofrecería a los palestinos no era un Estado soberano independiente, sino tres bantustanes discontinuos separados por asentamientos israelíes y puestos de control militares, sin ningún derecho de retorno para los refugiados palestinos.

Israel mantendría el control sobre el espacio aéreo, la radio, la cobertura de telefonía móvil y las fronteras de Palestina con Jordania, y conservaría sus bases militares en el 13,3% de Cisjordania, al tiempo que anexionaría el 9% e incluso mantendría tres bloques de asentamientos en Gaza que dividen el enclave en partes separadas.

El propio negociador y ministro de Asuntos Exteriores de Israel, Shlomo Ben Ami, dijo que si fuera palestino, habría rechazado las demenciales condiciones de Camp David. Eso no ha impedido que Israel siga afirmando desde entonces que la cumbre de 2000 fue su «oferta más generosa» y repitiendo el bulo de que «no tenemos ningún socio para la paz en Palestina» para legitimar la perpetuación del apartheid.

En 2005 Israel dejó claro que su redespliegue de tropas en Gaza y el traslado simbólico de 9.000 colonos de Gaza a Cisjordania tenían como objetivo «congelar el proceso de paz» e «impedir el establecimiento de un Estado palestino».

Un año más tarde Ehud Olmert se convirtió en primer ministro y el presidente de la Autoridad Palestina, Abbas, intentó acercarse a él para entablar conversaciones de paz. Un alto funcionario israelí declaró a The New Arab que Abbas se pasó 16 meses implorando a Olmert que hablara con él y negociara, pero este último siguió postergando la cuestión.

Finalmente, cuando comenzaron a salir a la luz los problemas legales de Olmert, este se embarcó en una acción destinada a dejar huella negociando una propuesta similar a la de Camp David, al tiempo que lanzaba la guerra más sangrienta contra Gaza hasta ese momento, la Operación Plomo Fundido.

Tras 36 reuniones en las que los palestinos hicieron todo lo posible por llegar a un acuerdo, Olmert tuvo que dimitir de su cargo y Netanyahu le sucedió.

Las repetidas propuestas de Hamás

Una de las piedras angulares de los argumentos de Israel para mantener el apartheid ha sido la ridiculizada mentira de que «dejamos Gaza y a cambio recibimos los cohetes de Hamás».

Israel también culparía del colapso del proceso de paz a los ataques de Hamás en la década de 1990, aunque el primer ataque importante de Hamás en 1994 en la estación de autobuses de Hadera, en el que murieron cinco personas, se produjo sólo después de la masacre de la mezquita de Ibrahim, en la que 29 fieles palestinos fueron asesinados durante la oración por el colono israelí Baruch Goldstein.

Al igual que la OLP, Hamás también hizo varias ofertas de paz a Israel, aunque con mayor cautela. Los líderes del grupo vieron que la Autoridad Palestina había reconocido a Israel, abandonado la resistencia armada y colaborado con las agencias de seguridad israelíes contra sus propios compatriotas palestinos, aunque no había recibido nada a cambio y había perdido toda influencia o herramienta de presión para obtener concesiones significativas de Israel.

Por lo tanto, el punto de partida de Hamás en las negociaciones fue un alto el fuego de entre 10 y 30 años que incluía el cese total de las hostilidades sin desarme.

Cuando Hamás hizo esta oferta en 1997, Israel respondió de inmediato intentando asesinar al máximo líder político del grupo, Jaled Meshal, en Jordania. Cuando el fundador de Hamás, Ahmed Yassin, reiteró la oferta en 2004, Israel lo asesinó dos meses después. Más tarde, funcionarios israelíes admitirían que podrían haber hecho las paces con Hamás bajo el liderazgo de Yassin.

De manera similar, cuando el máximo comandante militar de Hamás, Ahmad Al-Yabari, comenzó a promover una propuesta de alto el fuego permanente, Israel lo asesinó en 2012. Haaretz calificó a Yabari como «el subcontratista de Israel en Gaza», ya que hizo todo lo posible por proporcionar tranquilidad a Israel durante los alto el fuego y evitar que otros grupos armados violaran esta calma.

En 2006, tan pronto como Hamás formó un gobierno, el entonces primer ministro Ismael Haniyeh envió una carta a la administración Bush ofreciendo un compromiso con Israel basado en la solución de dos Estados.

El asesor de Haniyeh, Ahmad Yusef, presentó una propuesta de paz demasiado indulgente, que el partido Fatah del presidente Abbas calificó de «peor que la declaración Balfour». Se basaba en el establecimiento de un Estado palestino con fronteras temporales en un tercio de Cisjordania (zonas A y B) y la Franja de Gaza, para luego ampliar lentamente los límites del Estado mediante negociaciones y diplomacia.

Israel respondió imponiendo un bloqueo draconiano a Gaza y presionando a Suiza y al Reino Unido, que habían acogido a Yusef, para que le prohibieran a él y a cualquier líder de Hamás la entrada en sus países. También retuvo los ingresos de la Autoridad Palestina para llevar a la quiebra y al colapso al gobierno de Hamás en Gaza. Tel Aviv y Estados Unidos comenzaron entonces a tramar un golpe de Estado para derrocar a Hamás.

En 2008 Hamás se comprometió con un colono israelí, el rabino Menachem Froman, a formular una propuesta de alto el fuego que levantara el asedio de Israel a Gaza y, a cambio, garantizara el cese total de las hostilidades.

Hamás aceptó la propuesta final, Israel la rechazó de plano y, más tarde ese mismo año, lanzó la Operación Plomo Fundido, cuyo objetivo era, según la ONU, «castigar, humillar y aterrorizar» a la población civil de Gaza.

El Instituto Estadounidense de la Paz informó en 2009 que Hamás había «enviado repetidas señales de que podría estar dispuesto a iniciar un proceso de coexistencia con Israel».

Incluso durante el actual genocidio de Israel en Gaza, Hamás ha manifestado en repetidas ocasiones su voluntad de participar en un proceso político y se ha ofrecido a deponer las armas y desmantelar su ala militante si Israel pone fin a su ocupación. Alternativamente, ofrecieron una tregua de 10 años, pero Israel ha rechazado repetidamente esas propuestas.

Una fuente cercana a las negociaciones de alto el fuego en Gaza declaró a The New Arab que en 2024 Ismail Haniyeh entabló conversaciones con Estados Unidos para limitar Hamás a un partido político y participar en un proceso de paz. La fuente afirmó que el interlocutor de Haniyeh era el director de la CIA, Bill Burns. Israel asesinó inmediatamente a Haniyeh en Teherán tan pronto como comenzaron esas conversaciones.

El veredicto de la historia sobre el rechazo de Israel no lo escribirán los propagandistas de Tel Aviv ni los redactores de discursos de Washington, sino que quedará inscrito en el largo y sangriento libro de cuentas de oportunidades desperdiciadas, promesas incumplidas y traiciones deliberadas.

Cada negociador asesinado, cada acuerdo frustrado, cada reacción de pánico ante el más mínimo gesto simbólico de la soberanía palestina pone de manifiesto una verdad más profunda: los líderes israelíes temen más a la paz que a la guerra, porque la paz exigiría igualdad, responsabilidad y el fin del apartheid.

La cuestión ya no es si los palestinos lograrán la libertad o aceptarán la coexistencia, sino cuántas «oportunidades perdidas» más obligará Israel al mundo a soportar antes de que llegue ese día.

Muhammad Shehada es un escritor y analista palestino de Gaza y director de Asuntos de la UE en el Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor. X: @muhammadshehad2

Texto en inglés: The New Arab, traducido por Sinfo Fernández.

ENGLISH

Israel’s leaders fear peace more than war, because peace would require equality, accountability, and an end to apartheid.

When it comes to peace, Israel never misses an opportunity to miss an opportunity.

For more than half a century, the greatest obstacle to Middle East peace has not been the absence of bold Palestinian overtures, but the relentless Israeli determination to bury them before they can take root.

Time and again - from the Palestine Liberation Organisation’s (PLO) unprecedented 1988 recognition of Israel and renunciation of armed struggle, to Hamas leaders offering decade-long ceasefires - Palestinian leaders have placed historic compromises on the table.

And time and again, Israel has met these moments not with open hands, but with clenched fists, political sabotage, and assassinations. The pattern is so consistent, so deliberate, that “missing an opportunity for peace” has ceased to be a tragic accident and become a calculated doctrine.

In 1988, the Palestine Liberation Organisation gave Israel the most generous offer in Palestinian history. The PLO accepted the state of Israel, conceded 78% of historic Palestine to “a Jewish State,” and condemned “terrorism in all its forms” and asked in return for a state in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem.

This should’ve been Israel’s dream scenario: ending the conflict, the First Intifada, and its international isolation and securing its future in the region. However, Tel Aviv went into full panic mode instead.

Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir immediately rejected the PLO’s gesture, deeming it “crazy and dangerous” and vowing that Israel “will never permit the creation of an independent Palestinian state in the occupied territories”.

His Defence Minister, Yitzhak Rabin, pledged to use “an iron fist” to crush this peace offering. Israel’s Foreign Ministry activated a damage control team to smear the PLO’s proposal. The one Israeli journalist, David Grossman, who dared to report the PLO’s decision was sacked from his radio job and attacked in the Knesset and all over Israeli media.

Israel’s government and US pro-Israeli organisations also criticised American Jews who met Yasser Arafat to build on his peace gesture. The US denied Arafat a visa to present his offer at the UN General Assembly.

Today, history repeats itself, as European countries try to offer Israel a way out of its heavily damaged image from the Gaza genocide.

Last May in Singapore, French President Emmanuel Macron described recognising Palestine as “a moral duty and a political necessity,” then rendered that statement effectively hollow by conditioning such a symbolic gesture on Hamas disarming, leaving Gaza, and not playing any role in Palestinian governance.

The Israeli government again panicked and instantly accused Macron of “leading a crusade against the Jewish state”.

Tel Aviv has since been similarly attacking every country that expressed an intent to recognise Palestine, accusing them of “rewarding” Hamas, sabotaging ceasefire negotiations, and pushing Israel towards “national suicide”.

Israel’s frantic backlash is telling. Israelis understand that recognition is a European manoeuvre to revive a façade of a long-dead peace process and avoid confronting or holding Israel accountable for its genocide.

The recognition would not have an impact on advancing Palestinian statehood, nor would it restrain Israel’s accelerated annexation of the West Bank.

Yet even a simple gesture like this causes panic in Israel because Netanyahu is trying to persuade his Western allies that the only solution to the Palestinian question is Gaza’s depopulation.

Western leaders try to blame Israel’s rejectionism on Netanyahu’s far-right government. However, every single Israeli Zionist political party, including the leftist Meretz-Labour, has made clear its opposition to the two state solution.

This rejectionism is not new or the result of 7 October but has been a consistent feature of successive Israeli governments since its occupation began in 1967.

Thwarting Palestinian 'peace offensives'

In 1976, the PLO and Arab countries pushed for a resolution at the UN Security Council that called for the two state solution. The resolution received support from all UNSC members, but Israel rejected it, so the US vetoed it.

In 1981, the PLO officially endorsed a proposal from the Soviet Union for Palestinian statehood in the 1967 territories and Israel’s “security and sovereignty”. Months later, Saudi Arabia’s King Fahd offered Israel the most generous proposal possible; Israel would be integrated into the region and guaranteed peace from all Arab countries if it accepted the two state solution.

This offer was reiterated in 2002 as the ‘Arab Peace Initiative’ and endorsed by 57 Muslim countries, Israel ignored it.

Israel saw a threat in this momentum and regarded it as a “peace offensive”; Palestinians were becoming too moderate, and Israel was running out of excuses for maintaining the occupation.

Tel Aviv responded with war on the PLO in Lebanon in order to apply the “fiercest military pressures” to undermine Palestinian moderates and make the PLO more hardline “to halt its rise to political respectability”.

Oslo and the peace process sham

In 1993, Israel was compelled to accept the Oslo Accords by its failure to violently crush the First Intifada and its inability to cope with international isolation, pressure, and the economic, diplomatic, and political damage resulting from its “breaking the bones” strategy against unarmed civilian protesters and children.

The world hailed Oslo as a new era of peace, but Israel put enough loopholes in the agreement to avoid allowing an end to the occupation. Prime Minister Rabin, who won a Nobel Peace Prize for Oslo, made it abundantly clear that it was merely about separation, not Palestinian statehood.

“We do not accept the Palestinian goal of an independent Palestinian state between Israel and Jordan. We believe there is a separate Palestinian entity short of a state,” he said.

Apartheid means 'separateness', and this is what transpired on the ground. Israeli settlements grew exponentially, and more settlers moved into the occupied territory during the “peace process” than before Oslo. Palestinians, meanwhile, were forced to police Israel’s occupation and thwart armed resistance, making apartheid cost-free for Tel Aviv.

In 2000, Israel made clear at Camp David that the maximum it would offer Palestinians was not a sovereign independent state, but rather three discontiguous Bantustans separated by Israeli settlements and military checkpoints without any right of return for Palestinian refugees.

Israel would retain control over Palestine’s airspace, radio, cellphone coverage, and borders with Jordan, and maintain its military bases in 13.3% of the West Bank while annexing 9% and even keeping three settlement blocks in Gaza that cut the enclave into separate pieces.

Israel’s own negotiator and foreign minister, Shlomo Ben Ami, said if he were Palestinian, he would have rejected Camp David’s insane terms. That hasn't stopped Israel ever since from claiming the 2000 summit was its “most generous offer” and repeating the canard “we have no peace partner in Palestine” to legitimise making apartheid permanent.

In 2005, Israel made clear that its redeployment of troops in Gaza and symbolic transfer of 9,000 settlers from Gaza to the West Bank was about “freezing the peace process” and “prevent[ing] the establishment of a Palestinian state”.

A year later, Ehud Olmert became Prime Minister, and PA President Abbas attempted to approach him for peace talks. A top Israeli official told The New Arab that Abbas spent 16 months imploring Olmert to talk to him and negotiate while the latter kept procrastinating.

Eventually, when Olmert’s legal troubles began to surface, he engaged in a legacy-shaping act of negotiating a proposal that was similar to Camp David, while simultaneously launching the bloodiest war on Gaza at the time, Operation Cast Lead.

After 36 meetings where Palestinians bent backwards to get an agreement, Olmert had to resign from his position, and Netanyahu succeeded him.

Hamas' repeated overtures

A cornerstone of Israel's talking points for maintaining apartheid has been the debunked canard that “we left Gaza and got Hamas rockets in return”.

Israel would also blame the collapse of the peace process on Hamas attacks in the 1990s, although the first major Hamas attack in 1994 at the Hadera bus station that killed five people came only after the Ibrahimi Mosque massacre, when 29 Palestinian worshipers were murdered during prayer by Israeli settler Baruch Goldstein.

Like the PLO, Hamas also made several peace offerings to Israel, although more cautiously. The group's leaders saw that the PA had recognised Israel, abandoned armed resistance, and collaborated with Israeli security agencies against fellow Palestinians, but had received nothing in return and lost any leverage or tools of pressure to get meaningful concessions from Israel.

Hence, Hamas’ starting point in the talks was a 10 to 30-year ceasefire that included a full mutual cessation of hostilities without disarmament.

When Hamas made this offer in 1997, Israel immediately responded by attempting to assassinate the group’s top political leader, Khaled Meshal, in Jordan. When Hamas’ founder Ahmed Yassin reiterated the offer in 2004, Israel assassinated him two months later. Israeli officials would later admit they could have made peace with Hamas under Yassin.

Similarly, when Hamas’ top military commander, Ahmad Al-Jabari, began to advance a permanent ceasefire proposal, Israel assassinated him in 2012. Haaretz called Jabari “Israel’s subcontractor in Gaza,” since he went to great lengths to provide Israel with calm during ceasefires and prevent other armed groups from violating this calm.

In 2006, as soon as Hamas formed a government, then Prime Minister Ismael Haniyeh sent a letter to the Bush administration offering a compromise with Israel based on the two state solution.

Haniyeh’s advisor, Ahmad Yousef, made a peace proposal that was too lenient, with President Abbas’ Fatah party calling it “worse than the Balfour declaration”. It was premised on establishing a Palestinian state with temporary borders on a third of the West Bank (Area A and B) and the Gaza Strip, then slowly expanding the boundaries of the state through negotiations and diplomacy.

Israel responded by imposing a draconian siege on Gaza and pressuring Switzerland and the UK, which had hosted Yousef, to ban him and any Hamas leaders from entering their countries. It also withheld the PA’s revenues to bankrupt and collapse Hamas’ government in Gaza. Tel Aviv and the US then began plotting a coup to overthrow Hamas.

In 2008, Hamas engaged with an Israeli settler, Rabbi Menachem Froman, to formulate a ceasefire proposal that would lift Israel’s siege on Gaza and, in return, ensure a full cessation of hostilities.

Hamas accepted the final proposal, Israel rejected it out of hand, and later that year launched Operation Cast Lead, whose goal was to “punish, humiliate and terrorise” Gaza’s civilian population, per the UN.

The US Institute of Peace reported in 2009 that Hamas had “sent repeated signals that it may be ready to begin a process of coexisting with Israel”.

Even during Israel’s genocide on Gaza, Hamas has repeatedly stated its willingness to engage in a political process and offered to lay down its arms and dismantle its militant wing if Israel ends its occupation. They alternatively offered a 10-year truce, but Israel has repeatedly rejected those proposals.

A source close to the Gaza ceasefire negotiations told The New Arab that in 2024, Ismail Haniyeh engaged in talks with the US on restricting Hamas to a political party and engaging in a peace process. The source said Haniyeh’s interlocutor was CIA director Bill Burns. Israel immediately assassinated Haniyeh in Tehran as soon as those talks began.

History’s verdict on Israel’s rejectionism will not be written by propagandists in Tel Aviv or speechwriters in Washington - it will be inscribed in the long, bloodstained ledger of squandered chances, broken promises, and deliberate betrayals.

Every murdered negotiator, every scuttled accord, every panic-stricken backlash to even the most symbolic gesture of Palestinian statehood exposes a deeper truth: Israel’s leaders fear peace more than war, because peace would require equality, accountability, and an end to apartheid.

The question is no longer whether Palestinians will achieve freedom or accept coexistence, but how many more “missed opportunities” Israel will force the world to endure before that day arrives.

Muhammad Shehada is a Palestinian writer and analyst from Gaza and the EU Affairs Manager at Euro-Med Human Rights Monitor.

Follow him on Twitter: @muhammadshehad2

Israeli rape culture. Cultura israelí de la violación sexual. ENG ESP

Zionism is inherently imbued with rape culture. El sionismo como cultura de la violación

Publicado hoy.

Vídeo. "Genocidio en Palestina. Un espejo dramático que impacta en la sanidad española" Vídeo 90 min

Encuentro en Zaragoza, preparación para el Tribunal de los Pueblos sobre la Complicidad con el Genocidio palestino en el Estado español TPCGP-25.

Publicado hace 2 días.

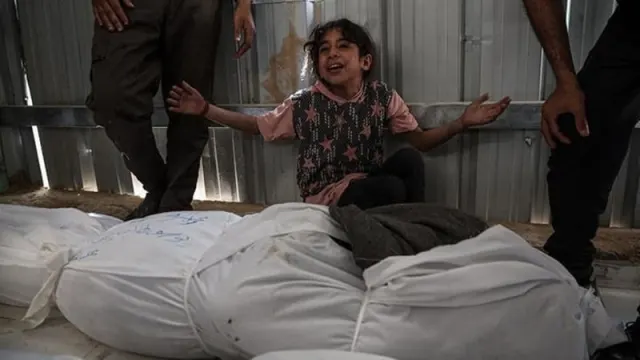

Gaza’s Orphan Crisis: 40,000. En Gaza, 40.000 huérfanos ENG ESP

40,000 children after losing one or both parents. 40.000 niños en Gaza sin uno o dos padres

Publicado hace 7 días.

Teva y el ejército de Israel (IDF). Teva and the Israel Defense Forces (IDF). ESP ENG

Teva apoya directamente el genocidio palestino. Teva directly supports the genocide against Palestinians.

Publicado hace 14 días.

ICE operations (USA) versus Israel occupation of Gaza. EEUU, policía de inmigración versus Israel ocupación de Gaza. ENG ESP

“Imperial-colonial boomerang” in action. El «bumerán imperial-colonial» en acción

Publicado el 13 de febrero.

Teva, growing global backlash. Teva, boicot creciente ENG ESP

Teva: politics and business over compassion and ethics. Teva: política y negocio sobre compasión y ética

Publicado el 10 de febrero.

"Si Francesca Albanese es terrorista, yo también". "If Francesca Albanese is a terrorist, then so am I" ESP ENG

"Una relatora de derechos humanos de la ONU, tratadа como terrorista por documentar el genocidio en Gaza". "A UN human rights rapporteur, treated as a terrorist for documenting the genocide in Gaza"

Publicado el 9 de febrero.

Vídeo, 60 sg. Dr. Hussam Abu Safiya. Lazos Rojos por la liberación de rehenes palestinos.

Campaña por la liberación de rehenes palestinos

Publicado el 7 de febrero.Ver más / See more