"Death, death to the IDF" (Israel Defense Force). "Muerte, muerte a las fuerzas armadas de Israel" ENG ESP

ENGLISH

Death, death to the IDF (Israel Defense Force)

"Death to the IDF": UK band Bob Vylan sparks outrage over Glastonbury chant. The singer concluded, “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free, inshallah”.

Bob Vylan led chants of “death to the IDF” and “free, free Palestine” during a provocative set at Glastonbury 2025.

NOTE

We have the right to express our thoughts directly; we don't have to be "correct" or mince words.

In France occupied by Nazi Germany, wasn't the normal to think "death, death to the Gestapo" or "death, death to the Wehrmacht"? The opposite was to be with the Vichy Regime, with its collusion and collaboration.

The IDF violates all international law; they have been the enforcer of murderous, colonialist, and racist Zionism for decades. They are terrorists, terrorists of the State of Israel, a terrorist state. They bomb with impunity, they burn alive those unable to defend themselves, they shoot children in the head, dismember them, blow up women, destroy buildings and tents, eliminate water sources, their planes, drones, tanks, and snipers target healthcare workers, educators, and journalists... they are cowards, they won't stand up to an army, and now they are finishing the "job" with genocide, hour after hour, without rest, without mercy...

If we lived in Palestine, the minimum cry would be "DEATH, death to IDF," and the desire would be to have an armed force, including air and anti-aircraft forces, that could defend us.

We are left with words. Are we going to cut them back?

28 June 2025

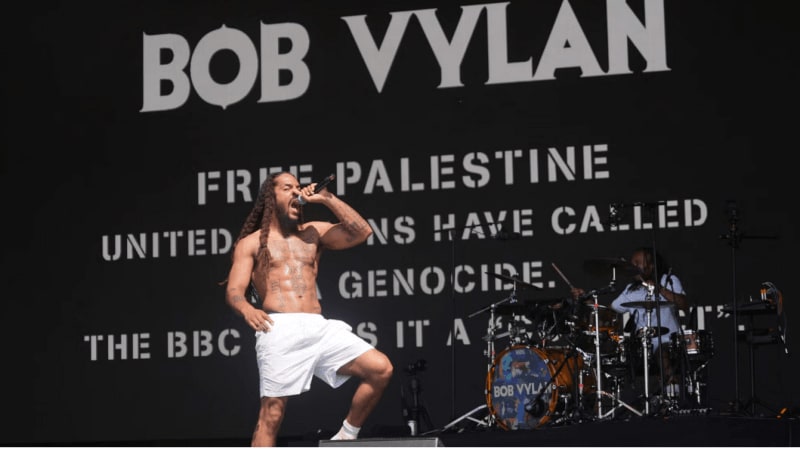

On a day of political statements at Worthy Farm, Bob Vylan played a set on the West Holts Stage on Saturday afternoon (June 28) immediately before the much-anticipated Kneecap appearance and led the capacity crowd through a raucous performance.

The set saw frontman Bobby Vylan call for solidarity with bands that “use their platform to speak up for the Palestinian people”, namechecking Kneecap, The Murder Capital and Amyl & The Sniffers in particular.

He also said that he was aware that the performance was being streamed on the BBC and so he would not say anything “too extreme”, adding that he would “leave that to those lads”, referring to “their mates Kneecap”.

After the crowd instigated a chant of “free, free Palestine”, which they did multiple times, Bobby said, “Have you heard this one?”, before leading a chant of “death, death to the IDF”, referring to the Israeli Defense Forces, which are involved in the ongoing war in Gaza.

Bobby also said: “We are not pacifist punks here over at Bob Vylan Enterprises,” referencing lyrics from their 2023 single ‘Censored (Interlude)’. “We are the violent punks, because sometimes you gotta get your message across with violence because that is the only language some people speak, unfortunately.”

Throughout the performance, political slogans were projected onto the screen behind them, including “Free Palestine – United Nations have called it a genocide – the BBC calls it a ‘conflict’”.

Authorities had closed off access to the stage beforehand due to the demand to see the Irish rap trio that have been at the centre of a storm of controversy in recent months, with their set starting just half an hour after Bob Vylan’s.

Kneecap went on to deliver an incendiary set in which they again accused Israel of “committing genocide against the Palestinian people, aided by the UK government”. They also took aim at Prime Minister Keir Starmer, as well as Rod Stewart for his recent comments in support of Nigel Farage.

Others to use their platform to speak out at Glastonbury 2025 include Amyl & The Sniffers, who took on colonisation, the war in Palestine, AI and J.K. Rowling in their fiery set on the Other Stage on Saturday. Inhaler and CMAT also made pro-Palestine remarks on Friday, among others.

So who are Bob Vylan?

The duo are Bobby Vylan, the frontman, and drummer Bobbie Vylan. They have not revealed their real names to protect their privacy.

They formed in Ipswich in 2017 and their musical style is a mix of punk, rap, and hard rock.

They have released three albums - We Live Here (2020), Bob Vylan Presents The Price Of Life (2022), and last year's Humble As The Sun - and their music has won them awards including best alternative act at the MOBOs in 2022, and best album at the Kerrang Awards in the same year.

Their songs confront issues including racism, homophobia, toxic masculinity, and far-right politics, and the track Pretty Songs is often introduced by Bobby saying that "violence is the only language that some people understand".

Gigs often include some crowd-surfing from the frontman, and they have collaborated with artists including Amyl And The Sniffers singer Amy Taylor, Soft Play guitarist Laurie Vincent, and rock band Kid Kapichi.

In an interview with The Guardian last year, Bobby Vylan told how he attended his first pro-Palestine protest at the age of 15, escorted by a friend's mother.

The duo have been outspoken on the war in Gaza and called out other acts seen as left-wing who haven't been showing the same amount of public solidarity.

The Glastonbury set

Before their appearance at the festival, the duo highlighted it to fans watching at home, posting on Facebook: "Turns out we're finally at a point where the BBC trust us on live tv! Watch us live either in the field or in the comfort of your own home!"

On stage, they performed in front of a screen bearing several statements, including one which claimed Israel's actions in Gaza amount to "genocide".

Afterwards, as controversy over the set grew, they appeared to double down with statements shared on social media.

REMEMBER

UNITED NATIONS, GENERAL ASSEMBLY: “Reaffirms the legitimacy of the struggle of peoples for independence, territorial integrity, national unity and liberation from colonial and alien domination and foreign occupation by all available means, including armed struggle” Resolution 34/44, 23 November 1979

Francesca Albanese: "Israel cannot claim the right to self-defence against a threat that emanates from a territory it occupies [Gaza], from a territory that is under belligerent occupation". Israel's right to self-defence is “non-existent” under international law as it is not under threat from another state.

🔻 When a singer at #Glastonbury chants “Death to the IDF”

The Western world erupts…

BBC apologizes, the government condemns, police investigate,

and the Israeli embassy is “deeply disturbed”!

🔺 But when #Gaza is bombed day and night,

Families wiped out, hospitals flattened,

Children pulled from rubble headless…

Silence reigns.

Or worse: “#Israel has the right to defend itself.”

🎭 The hypocrisy is stunning.

Chanting against bombs is a crime,

But dropping the bombs?

That's “freedom and democracy.”

ESPAÑOL

Actualización, 22 agosto 2025: El actor Javier Bardem llama "nazis" a las Fuerzas de Defensa de Israel Asimismo, el actor acompaña sus palabras con un vídeo en el que aparece cómo dispara un tirador contra un grupo de personas.

NACIONES UNIDAS, ASAMBLEA GENERAL: «Reafirma la legitimidad de la lucha de los pueblos por la independencia, la integridad territorial, la unidad nacional y la liberación de la dominación colonial y extranjera y de la ocupación extranjera por todos los medios disponibles, incluida la lucha armada» Resolución 34/44, 23 de noviembre de 1979.

Francesca Albanese: «Israel no puede reivindicar el derecho a la legítima defensa frente a una amenaza que emana de un territorio que ocupa [Gaza], de un territorio que está bajo ocupación beligerante». El derecho de Israel a la legítima defensa es «inexistente» en virtud del derecho internacional, ya que no está amenazado por otro Estado.

🔻 Cuando un cantante en #Glastonbury canta «Muerte a las FDI»

El mundo occidental estalla...

¡La BBC se disculpa, el gobierno condena, la policía investiga,

y la embajada israelí está «profundamente perturbada»!

🔺 Pero cuando #Gaza es bombardeada día y noche,

Familias aniquiladas, hospitales arrasados,

Niños sacados de los escombros sin cabeza...

Reina el silencio.

O peor: «#Israel tiene derecho a defenderse».

🎭 La hipocresía es impresionante.

Cantar contra las bombas es un crimen,

¿Pero lanzar las bombas?

Eso es «libertad y democracia».

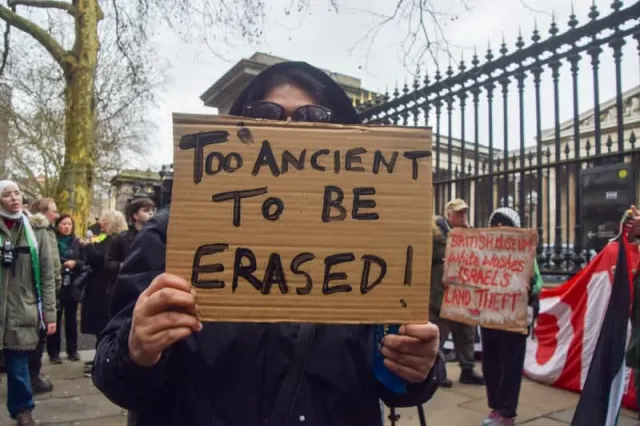

The British Museum cannot erase Palestine. El Museo Británico no puede borrar "Palestina" ENG ESP

Publicado hace 2 días.

Adania Shibli, "Minor Detail", "Un detalle menor". Novel. Novela ENG ESP

Publicado hace 8 días.

Memoirs of a Palestinian Communist, Najati Sidq. Memorias de un comunista palestino. ENG ESP

Publicado el 13 de febrero.

“Epistemicide” in Gaza. Breaking the Chain of Knowledge. Epistemicidio en Gaza. Romper la cadena del conocimiento. ENG ESP

Publicado el 12 de febrero.

Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza. Wasim Said. Desde Gaza, Testigo del Infierno del Genocidio. ENG ESP

Publicado el 8 de febrero.

Malak Mattar. Gaza Artist and Survivor. Artista gazaití, y sobreviviente. ESP ENG

Publicado el 30 de enero.

"Cuando el mundo duerme". Ensayo. Francesca Albanese

Publicado el 29 de enero.

'Fire in Every Direction' Tareq Baconi ENG ESP

Publicado el 29 de enero.Ver más / See more