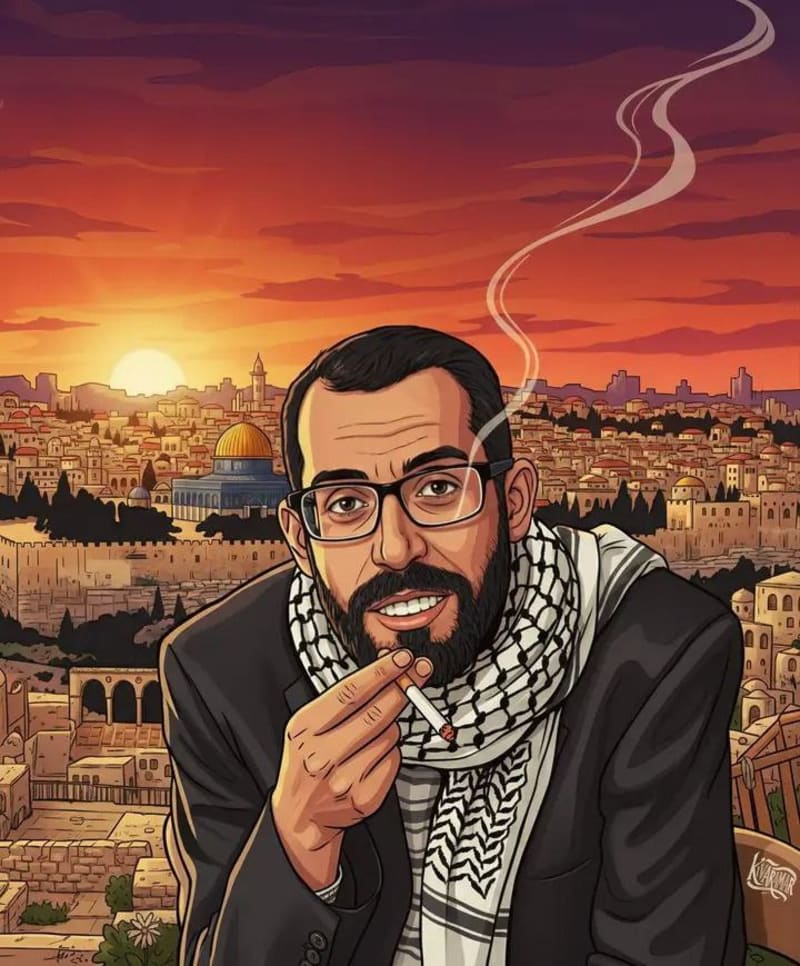

Bassel al-Araj. "I Have Found My Answers". Essay. "He encontrado mis respuestas". Ensayo. ENG ESP

ENGLISH

"I Have Found My Answers" Bassel al-Araj

This essay is by the Palestinian writer, teacher, and activist Bassel al-Araj, from his book I Have Found My Answers (وجدت أجوبتي), which was published posthumously in 2018.

About the writer

In 2011, Bassel al-Araj was arrested with five other Palestinian “Freedom Riders” for boarding a settler-only bus travelling to occupied East Jerusalem to challenge Israel’s apartheid policies.

He was arrested by the Palestinian Authority in 2016, charged with planning attacks against Israel. He was released after several months, after which Israeli forces tracked him and surrounded him in an apartment where he engaged in a two-hour gunfight. He was killed after his ammunition was depleted.

Some Palestinian activists refer to him as “the educated martyr” or “the educated engager” (المثقّف المُشتَبِك). He is known to have said: “If you want to be educated, you have to be an educated ‘engager’. If you are not willing to engage, you and your education are of no use.” (إذا بدك تصير مثقف لازم تصير مثقف مشتبك، وإذا بدكاش تشتبك ما في فايدة منك ولا من ثقافتك)

Live Like a Porcupine and Fight Like a Flea

In 1895, the psychologist James Mark Baldwin used the term “social accommodation” to refer to a biological adaptation in which a social equilibrium is created as a form of adjusting to the surrounding conditions. “Social accommodation” is generally defined as a social process that aims to reduce or avoid conflict. It’s a process of social conformity that leads to the end of conflict between groups because it reinforces either temporary or permanent peaceful interaction.

As for the psychological aspects of social accommodation, he refers to how individuals and groups respond to conflict by avoiding all forms of hostility. Economic, social, and psychological compensations are granted to one of the minority groups. Sociologists differentiate between “adaptation” and “accommodation”, where “adaptation” is used when the surrounding conditions are natural or organic.

Accommodation can be achieved through several means: coercion, arbitration, settlement, or even the ability to endure. Later, Ernst Haeckel used the term “ecology” to refer to the relationship between the organism and its organic and non-organic surrounding environment. Ecology studies the interdependent relationships between organisms and their surrounding environment.

I do not know when nor why a strange relationship developed between the Palestinian (I’m referring broadly to people of the Levant region and not just Mandate Palestine) and the porcupine. Was it because of the desire to hunt these porcupines, with its delicious flesh and myths about its therapeutic properties and the virility it bestows, or was it related to the porcupine’s destruction of the peasants’ crops?

The Indian crested porcupine (النيص) is a mammal of the rodent species, closely related to the hedgehog but bigger in size. It has several common names. It is referred to as al-shayham (الشيهم) in standard Arabic, and its scientific name is “Hystrix indica”. It carries short and long quills ranging between 10 and 35 centimetres, and it uses them for self-defence. It weighs between 4 and 16 kilograms. (It has very tasty meat, and I recommend not missing it if you get the chance)

The porcupine is a nocturnal animal that lives in a burrow underground. The burrow is relatively large and has many long tunnels with entrances and exits and what look like resting spots. When getting in and out of the burrow, the porcupine uses several specific and determined routes, as if carefully planned. It has a strange sense of paranoia, or what we Palestinians refer to as the “security sense”. (One of the main researchers who studied the porcupine was S. H. Prater). The species found in our lands are strictly herbivorous, and they mostly feed on colocynth (الحنظل) [also commonly known as Abu Jahl’s melon, bitter apple, and bitter cucumber]. It’s not recommended to shoot it when hunting as its spleen and liver could burst, making its meat taste very bitter.

The porcupine has a strong presence in Palestinian popular memory and stories. In Palestine, peasants have spun endless stories around it, describing the porcupine as a strange creature that cries and wails and, like human beings, has wishes and hopes. Like us, when a porcupine gets angry, it will throw the quills it carries on its neck and back at the enemy, accurately hitting them. At night, it roams alone, slowly and meditatively, and is attracted to smells, fruits, and roots. It is a private, silent being, but also a crybaby. It is a lonely, unique being. Its pain runs deep and its grudges, even deeper—just like its hunter.

Learning the behaviour of your prey is the first lesson in hunting.

Palestinians closely observed these porcupines and learnt everything about them. (In my life, I have gone on two porcupine hunting trips, and we were blessed with an abundant catch that we did not share with anyone). The hunter needs to adapt (and not to accommodate himself) to the life and behaviour of its prey to be able to catch it. But what happened is that the Palestinian so completely adopted the porcupine’s traits and tendencies, especially when in danger, that he ended up living like a porcupine.

On one Eid al-Adha holiday, my family sacrificed five sheep, and I was allowed to slaughter some of them and help in skinning and cutting the meat. The sheep were infested with fleas that attacked me. I tried many times to kill a flea on my body without any success. The only outcome of my attempts was that I got tired and paranoid. The only thing that helped was taking a full and thorough bath where I combed my body using hot water and soap, leading to a decisive victory.

The flea is a small flightless insect of the “Siphonaptera” species. It mostly lives as a parasite on a host, often a mammal. Its length ranges from 1 to 4 millimetres, and it moves by jumping using its two long hind legs. The flea bites its host, and the bites leave slightly raised, very itchy red spots.

The flea has an impressive combat strategy and fascinating tactics and techniques. It stings and jumps, then resumes stinging and skillfully avoids the hand or foot trying to crush it. It does not aim to kill its opponent (in the sense of fully eliminating the enemy system, for example, a dog) but rather to exhaust it, feed off it, disturb, and provoke it, preventing it from resting while damaging its nerves and morale. To achieve this, the flea needs time to reproduce. What starts as a localised infection will eventually become a widespread epidemic as the fleas multiply and sting areas closer and closer together.

Mao Zedong said: “When the enemy advances, we retreat. When they camp, we harass. When they are tired, we attack. When they retreat, we pursue them.” Zedong’s theory of guerrilla warfare resembles what could be described as a “flea war”.

Mao solved the dilemma, “how can a non-industrial nation defeat an industrial nation?”. [Friedrich] Engels saw the nation with more capital as being more capable of defeating its enemies. He thought that economic power is what determines the outcome of battles—it can provide the capital needed to manufacture arms.

Mao’s solution emphasised the intangible elements. Powerful nations with big armies typically focus on tangible elements like weapons, logistics, and soldier count; however, Mao, according to [Edward L.] Katzenbach, focused on the elements of time, space, and will. Going back to Mao’s previous quote, he avoided battle by giving up territory and, in doing so, exchanged space for time and used time to cultivate will. This is the essence of guerrilla warfare.

To return to our analogy, guerrilla forces engage in war exactly like fleas. The powerful, highly organised enemy suffers from the same vulnerabilities and weaknesses of the host with fleas: they have a large area to defend from a very tiny, very mobile enemy, who is spread everywhere and is hard to capture. If the battle lasts long enough, the host will eventually collapse on the battlefield from fatigue and blood loss, without having found anyone to attack.

Robert Taber explains it this way: “In practice, the dog (or the host) does not die of anemia. He merely becomes too weakened—in military terms, overextended; in political terms, too unpopular; in economic terms, too expensive—to defend himself. At this point, the flea would have multiplied to a veritable plague of fleas through a long series of small victories, each drawing its drop of blood.”

So live like a porcupine and fight like a flea!

ESPAÑOL

Databases for Palestine (genocide). Base de datos de Palestina (genocidio). ENG ESP

Publicado ayer.

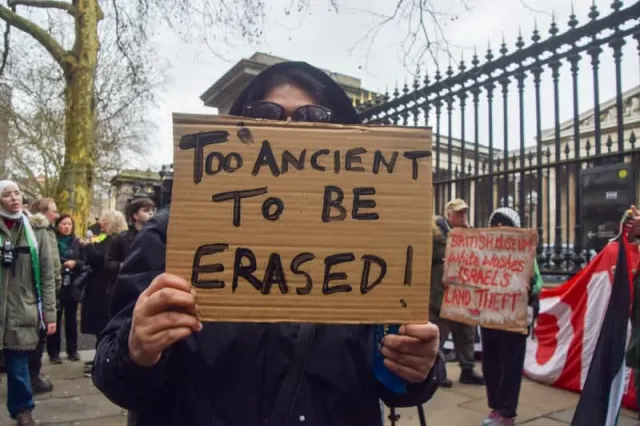

The British Museum cannot erase Palestine. El Museo Británico no puede borrar "Palestina" ENG ESP

Publicado hace 5 días.

Adania Shibli, "Minor Detail", "Un detalle menor". Novel. Novela ENG ESP

Publicado hace 11 días.

Memoirs of a Palestinian Communist, Najati Sidq. Memorias de un comunista palestino. ENG ESP

Publicado el 13 de febrero.

“Epistemicide” in Gaza. Breaking the Chain of Knowledge. Epistemicidio en Gaza. Romper la cadena del conocimiento. ENG ESP

Publicado el 12 de febrero.

Witness to the Hellfire of Genocide: A Testimony from Gaza. Wasim Said. Desde Gaza, Testigo del Infierno del Genocidio. ENG ESP

Publicado el 8 de febrero.

Malak Mattar. Gaza Artist and Survivor. Artista gazaití, y sobreviviente. ESP ENG

Publicado el 30 de enero.

"Cuando el mundo duerme". Ensayo. Francesca Albanese

Publicado el 29 de enero.Ver más / See more