ENGLISH

Tareq Baconi talks about his new memoir 'Fire in Every Direction'

Author Interviews NPR

November 4, 2025

Leila Fadel

7-Minute Listen

Transcript

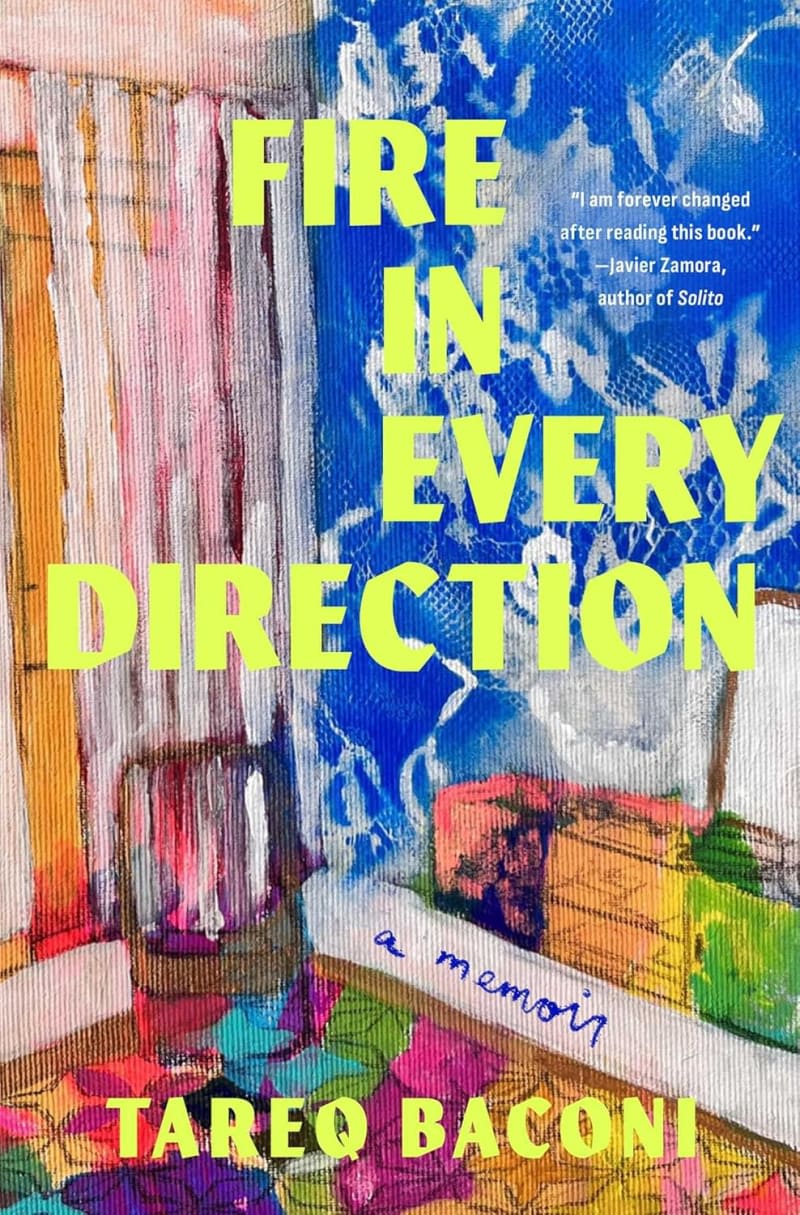

NPR's Leila Fadel speaks to Tareq Baconi, a Palestinian scholar. His memoir, "Fire in Every Direction," explores queer identity, family history, and political awakening.

LEILA FADEL, HOST:

A grandmother flees Palestine as a child on a fisherman's boat. A family is uprooted from Lebanon after a massacre of refugees. A writer grows up with a culture of silence in Jordan. Tareq Baconi, a renowned Palestinian scholar, has written a memoir of three generations of displacement. It's called "Fire In Every Direction," and Tareq Baconi is with me now. Thank you for being here.

TAREQ BACONI: Thank you for having me.

FADEL: So in your book, you start with unpacking a yellow box full of letters from a childhood friend named Ramzi. Who was he to you?

BACONI: Well, Ramzi was the first boy that I fell in love with, and we were each other's - in some ways, I mean, it's funny to say that because we were neighbors but also pen pals because we used to write each other letters the whole time that we knew each other.

FADEL: Central to this book is growing up in Amman, Jordan, you really keep part of who you are and yourself a secret, almost even from yourself. And you start to fall in love with this boy, Ramzi. And you describe it as wearing a mask. What happens when you start to peek out from behind the mask and confess your feelings?

BACONI: Well, I mean, the mask was also something that protected me in the sense that I was afraid of what it would mean to acknowledge these feelings, and the mask would help me pretend that everything was as it should be. And that was sort of increasingly unsustainable until I teased the mask off a bit and tried to write to him about my feelings, and the reaction was swift and brutal, and that was the last time we spoke.

FADEL: Throughout the book, you use this Arabic word ayb - shame - you know, which I'm very familiar with too. Arab American woman growing up and you just like, oh, I - this is ayb. You can't do this. You can't be like this. And that was sort of the start of your mother's life with your father, right? Like, oh, you can't just be dating now that you're in Jordan. We don't do this. You have to get married. And I just wonder, like, that theme, how it shaped the narrative.

BACONI: Well, I mean, the notion of ayb - of shame - I think is very oppressive and it's very resilient wherever you are, whether you're growing up in an Arab family in the U.S. in the West or back home. I think the strictures of ayb are very confining. But I think that notion of shame I was really attracted to it or interested in it because I just - it's completely shaped my life - my experience as a queer boy growing up, my mom's experience as a political feminist who's working to organize and to be a committed activist. The same notions of ayb shape us.

FADEL: So in college in London in 2003, you're going through this political awakening, but you've also been going through this very personal awakening for yourself. And there's a point where you tell your mother, you know, I'm a gay man, and she listens and she hears you. And she says, OK, we got to tell your dad.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: And you go back and tell your dad. What was that conversation like?

BACONI: It was very difficult. I knew that that was the beginning of a journey for them and a continuation of one for me. And so I was prepared to not see him for a long time after that. I approached it with a lot of trepidation, and actually, my mom did as well because she put sedatives in his coffee to make sure.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: Just drug him a little for this one.

BACONI: (Laughter) Just drug him a little, which, you know, in hindsight, Arab mama in an Arab home, she knows what she's doing.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: Oh, man.

(LAUGHTER)

FADEL: When you tell your dad, he says - and you said damaging things, and I'm sure this was hurtful to hear. He says you cannot live in Jordan anymore, that this is no longer the place for you. When you go to Haifa and find your grandmother's childhood home that she was displaced from in 1948, you cannot bring yourself to ring the doorbell. It seemed like you were searching for home. Have you found that?

BACONI: Yes. I have. I have found that. My concept of home now is in my chosen family. And then home has come to mean something else to me. It's not this sense of needing to go back to somewhere. I think it's - my concept of it has evolved.

FADEL: It was very heartwarming to read near the end of the book where your dad just, like, loves your husband. He's like, when are you coming back to Beirut? It's just a totally - like, it - things changed, like, once you were open and clear to them about who you were and that you wouldn't back down from who that was.

BACONI: Absolutely. I think that he surprised me in so many ways. My dad has passed now but, you know...

FADEL: I'm so sorry.

BACONI: ...Before he passed away, I just couldn't believe where he got to and how he embraced me. And it really affirmed my impulse that, you know, these silences, who are they serving? My relationship with my father is much, much - or was much more loving and more honest than it ever was when I was hiding parts of myself from him.

FADEL: Yeah. Your first book is a very well-known book called "Hamas Contained" - a totally different book than the one I read. What was it like writing such a personal work that speaks to this larger question around displacement and loss and war and belonging?

BACONI: It was challenging in ways that I hadn't necessarily anticipated. You know, writing analytically or writing academically is important, but it's also a way of hiding - at least it was for me.

FADEL: Yeah.

BACONI: And this book was a way of going into the lived experience. What does it mean that I'm the grandson of four refugees from Palestine, now having to witness a Nakba and being - or a genocide, the continuation of the Nakba - and being unable to stop it. And in that way, I found it painful but also cathartic and important for me on a personal level. You know, the funny thing is, I'm a very private person and I - you know, I would've never imagined writing a memoir. But actually, writing this book was the only way I could really confront myself and sit with myself and sort of embrace who I'd become as a person in all of its different facets.

FADEL: Is it freeing to have it in the world?

BACONI: Well, we'll find out. It's...

(LAUGHTER)

BACONI: You know, I keep saying this is either the bravest or the stupidest thing I've done, and we'll find out soon enough.

FADEL: Tareq Baconi is the author of "Fire In Every Direction." Thank you, Tareq.

BACONI: Thank you for having me.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

Nov 6 2025

Palestinian writer Tareq Baconi joins us to discuss his new memoir, Fire in Every Direction, a chronicle of his political and queer coming of age growing up between Amman and Beirut as the grandson of refugees from Jerusalem and Haifa.

While “LGBTQ+ labels have also been used by the West as part of empire,” with colonial projects seeking to portray Native populations as backward and in need of saving, “there’s a beautiful effort and movement among queer communities in the region to reclaim that language,” says Baconi. “I identify as a queer man today as part of a political project. It’s not just a sexual identity. It expands beyond that and rejects Zionism and rejects authoritarianism, and that’s part of my queerness.”

Baconi also comments on the so-called ceasefire agreement in Gaza and the election of Zohran Mamdani in New York City. “Palestinians are the ones that have to govern Palestinian territory, not this international force that comes in that takes any kind of sovereignty or agency away from the Palestinians,” he says.

ESPAÑOL

Tareq Baconi habla sobre sus nuevas memorias, 'Fire in Every Direction' "Fuego en todas direcciones"

Entrevista, transcripción.

4 de noviembre de 2025

Leila Fadel Escucha de 7 minutos Transcripción

Leila Fadel de NPR conversa con Tareq Baconi, académico palestino. Sus memorias, "Fuego en todas direcciones", exploran la identidad queer, la historia familiar y el despertar político.

LEILA FADEL, PRESENTADORA:

Una abuela huye de Palestina de niña en un barco de pescadores. Una familia es desarraigada del Líbano tras una masacre de refugiados. Un escritor crece en una cultura del silencio en Jordania. Tareq Baconi, reconocido académico palestino, ha escrito memorias sobre tres generaciones de desplazados. Se llama "Fuego en todas direcciones" y Tareq Baconi me acompaña. Gracias por estar aquí.

TAREQ BACONI: Gracias por la invitación.

FADEL: En tu libro, empiezas abriendo una caja amarilla llena de cartas de un amigo de la infancia llamado Ramzi. ¿Quién era él para ti?

BACONI: Bueno, Ramzi fue el primer chico del que me enamoré, y éramos el uno del otro; en cierto modo, es curioso decirlo porque éramos vecinos, pero también amigos por correspondencia, porque nos escribíamos cartas desde que nos conocimos.

FADEL: Un aspecto central de este libro es crecer en Amán, Jordania. Mantienes en secreto parte de ti mismo, casi incluso a ti mismo. Y empiezas a enamorarte de este chico, Ramzi. Y lo describes como si llevaras una máscara. ¿Qué sucede cuando empiezas a asomarte tras la máscara y a confesar tus sentimientos?

BACONI: Bueno, la máscara también me protegía, ya que me daba miedo reconocer estos sentimientos, y me ayudaba a fingir que todo era como debía ser. Y eso se volvió cada vez más insostenible hasta que me quité un poco la máscara e intenté escribirle sobre mis sentimientos, y la reacción fue rápida y brutal, y esa fue la última vez que hablamos.

FADEL: A lo largo del libro, usas la palabra árabe ayb (vergüenza), ya sabes, con la que también estoy muy familiarizada. Una mujer árabe-estadounidense que crece, y simplemente piensas: «Oh, esto es ayb. No puedes hacer esto. No puedes ser así». Y ese fue, en cierto modo, el comienzo de la vida de tu madre con tu padre, ¿verdad? Como: «Oh, no puedes simplemente salir con alguien ahora que estás en Jordania. No hacemos esto. Tienes que casarte». Y me pregunto cómo ese tema influyó en la narrativa.

BACONI: Bueno, creo que la noción de ayb —de vergüenza— es muy opresiva y muy resistente dondequiera que estés, ya sea que crezcas en una familia árabe en Estados Unidos, en Occidente o en tu país. Creo que las restricciones de ayb son muy restrictivas. Pero creo que esa noción de vergüenza me atrajo o me interesó mucho porque simplemente moldeó mi vida por completo: mi experiencia como chico queer de niño, la experiencia de mi madre como feminista política que trabaja para organizarse y ser una activista comprometida. Las mismas nociones de ayb nos moldean.

FADEL: Así que, en la universidad en Londres en 2003, estabas atravesando un despertar político, pero también un despertar muy personal. Y llega un momento en que le dices a tu madre: «Soy gay», y ella te escucha y te oye. Y dice: «Vale, tenemos que contárselo a tu padre».

(RISAS)

FADEL: Y tú regresas y se lo cuentas a tu papá. ¿Cómo fue esa conversación?

BACONI: Fue muy difícil. Sabía que era el comienzo de un viaje para ellos y la continuación de otro para mí. Así que estaba preparada para no verlo durante mucho tiempo después de eso. Lo afronté con mucha inquietud, y de hecho, mi mamá también, porque le puso sedantes en el café para asegurarse.

(RISAS)

FADEL: Solo drogámoslo un poco para esta ocasión.

BACONI: (Risas) Solo drogámoslo un poco, lo cual, ya sabes, en retrospectiva, una madre árabe en un hogar árabe, sabe lo que hace.

(RISAS)

FADEL: ¡Vaya!

(RISAS)

FADEL: Cuando se lo cuentas a tu papá, él dice... y dijiste cosas hirientes, y estoy segura de que fue doloroso escuchar eso. Dice que ya no puedes vivir en Jordania, que este ya no es tu lugar. Cuando vas a Haifa y encuentras la casa de la infancia de tu abuela, de la que fue desplazada en 1948, no te atreves a tocar el timbre. Parecía que buscabas un hogar. ¿Lo has encontrado?

BACONI: Sí. Lo he encontrado. Mi concepto de hogar ahora está en la familia que elegí. Y entonces, el hogar ha llegado a significar algo más para mí. No es esta sensación de necesitar volver a algún lugar. Creo que mi concepto de él ha evolucionado.

FADEL: Fue muy conmovedor leer cerca del final del libro que tu padre simplemente ama a tu esposo. Él dice: "¿Cuándo volverás a Beirut?". Es simplemente... las cosas cambiaron por completo, una vez que fuiste abierta y clara con ellos sobre quién eras y que no te arrepentirías de quién eras.

BACONI: Absolutamente. Creo que me sorprendió de muchas maneras. Mi padre ya falleció, pero, ya sabes...

FADEL: Lo siento mucho.

BACONI: ...Antes de que falleciera, no podía creer dónde había llegado y cómo me abrazó. Y realmente reafirmó mi impulso de que, ya sabes, estos silencios, ¿a quién sirven? Mi relación con mi padre es mucho, mucho, o era mucho más amorosa y honesta que cuando le ocultaba partes de mí.

FADEL: Sí. Tu primer libro es muy conocido, "Hamás Contained", un libro totalmente diferente al que leí. ¿Cómo fue escribir una obra tan personal que aborda esta cuestión más amplia en torno al desplazamiento, la pérdida, la guerra y la pertenencia?

BACONI: Fue un desafío que no necesariamente había previsto. Escribir analíticamente o académicamente es importante, pero también es una forma de esconderse, al menos para mí.

FADEL: Sí.

BACONI: Y este libro fue una forma de adentrarme en la experiencia vivida. ¿Qué significa para mí, nieto de cuatro refugiados de Palestina, tener que presenciar una Nakba y ser —o un genocidio, la continuación de la Nakba— y ser incapaz de detenerlo? Y, en ese sentido, lo encontré doloroso, pero también catártico e importante para mí a nivel personal. Lo curioso es que soy una persona muy reservada y... bueno, nunca me hubiera imaginado escribir unas memorias. Pero, en realidad, escribir este libro fue la única manera de confrontarme conmigo mismo, de reflexionar sobre mí mismo y, de alguna manera, aceptar quién me había convertido como persona en todas sus facetas.

FADEL: ¿Es liberador tenerlo en el mundo?

BACONI: Bueno, ya lo averiguaremos. Es...

(RISAS)

BACONI: Sabes, sigo diciendo que esto es lo más valiente o lo más estúpido que he hecho, y pronto lo sabremos.

FADEL: Tareq Baconi es el autor de "Fire In Every Direction". Gracias, Tareq.

BACONI: Gracias por invitarme.

(SONIDO DE MÚSICA)

Noviembre 6, 2025

"Fire in every direction", “Fuego en todas direcciones”: El autor palestino Tareq Baconi habla sobre Gaza, el sionismo y la aceptación de la identidad queer

El escritor palestino Tareq Baconi nos acompaña para hablar de sus nuevas memorias, Fuego en todas direcciones, una crónica de su madurez política y queer, creciendo entre Ammán y Beirut como nieto de refugiados de Jerusalén y Haifa.

Si bien “Occidente también ha utilizado las etiquetas LGBTQ+ como parte del imperio”, con proyectos coloniales que buscan retratar a las poblaciones nativas como atrasadas y necesitadas de salvación, “existe un hermoso esfuerzo y movimiento entre las comunidades queer de la región para recuperar ese lenguaje”, afirma Baconi.

“Hoy me identifico como un hombre queer como parte de un proyecto político. No se trata solo de una identidad sexual. Va más allá y rechaza el sionismo y el autoritarismo, y eso forma parte de mi identidad queer”.

Baconi también comenta sobre el supuesto acuerdo de alto el fuego en Gaza y la elección de Zohran Mamdani en la ciudad de Nueva York. “Los palestinos son los que tienen que gobernar el territorio palestino, no esta fuerza internacional que llega y les quita cualquier tipo de soberanía o capacidad de acción a los palestinos”, afirma.